Reflection and Documentation

CAPTO MUSICAE – CREATING SONIC AND MUSICAL THEATRE IN A CONTEMPORARY ARTISTIC CONTEXT

Øystein Elle

The National Norwegian Artistic Research Fellowship Programme 2013 – 2017

Norwegian Theatre Academy, Østfold University College

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ARTISTIC INTENTION

THE PROCESS

Text work

Collaboration

Composition

Extended vocal techniques

MAIN ARTISTIC RESULT

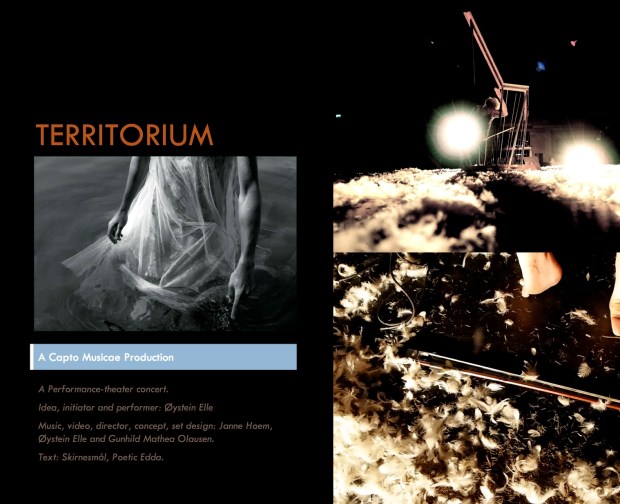

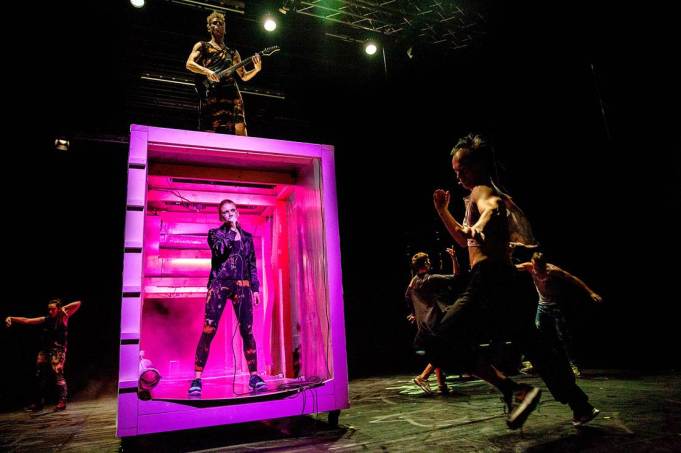

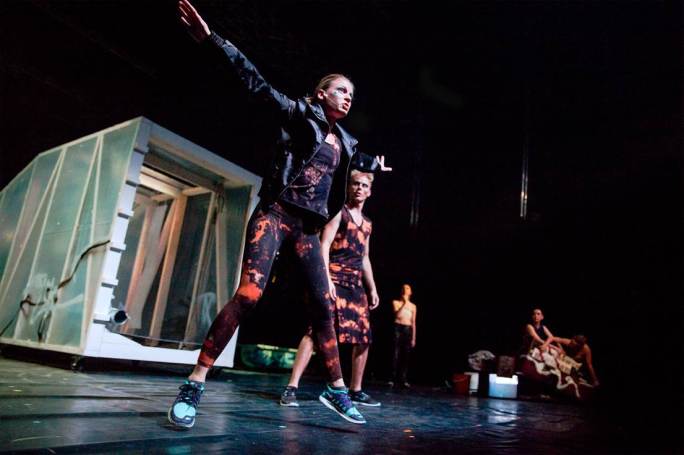

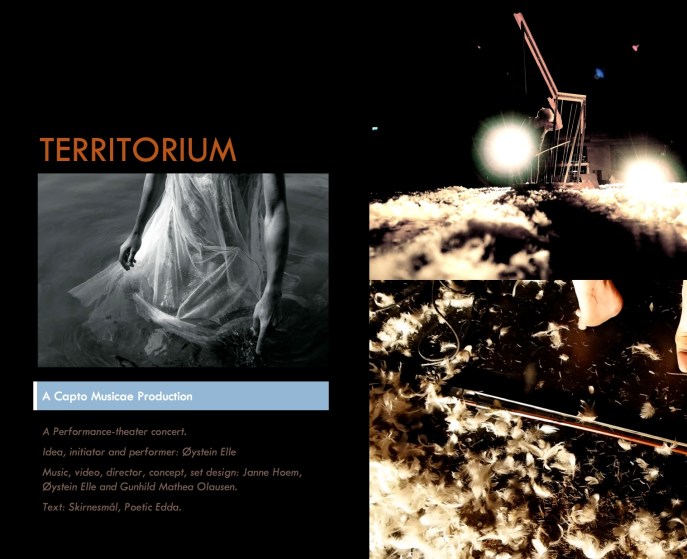

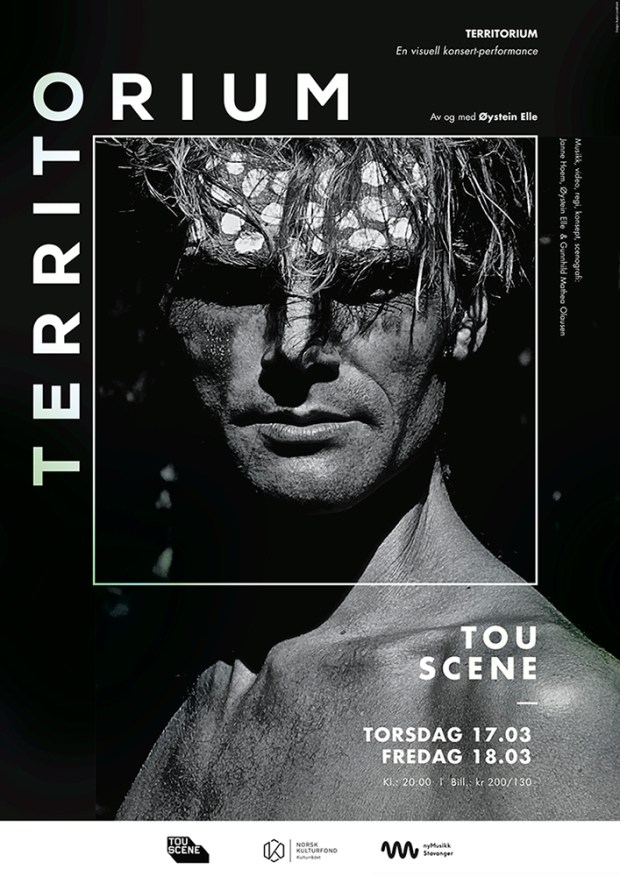

Territorium – A Visual Performance-Concert

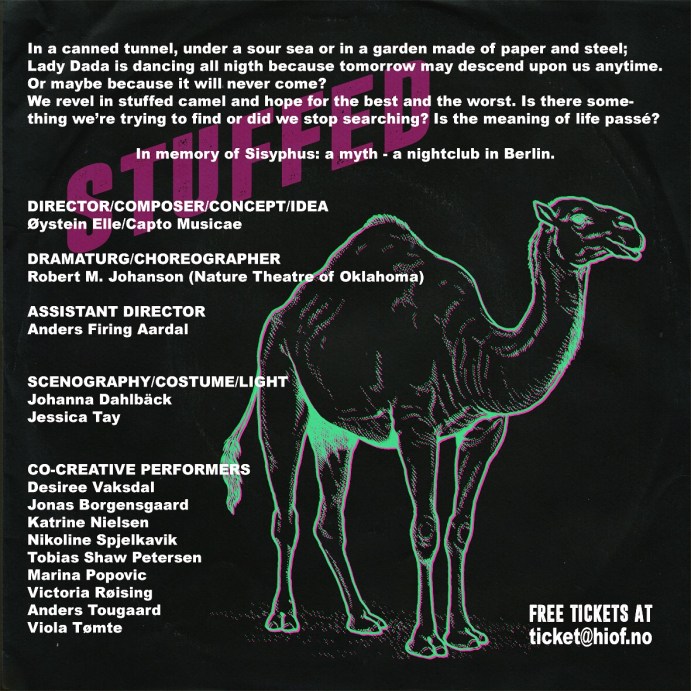

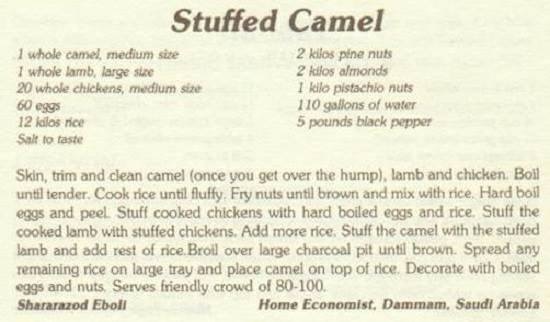

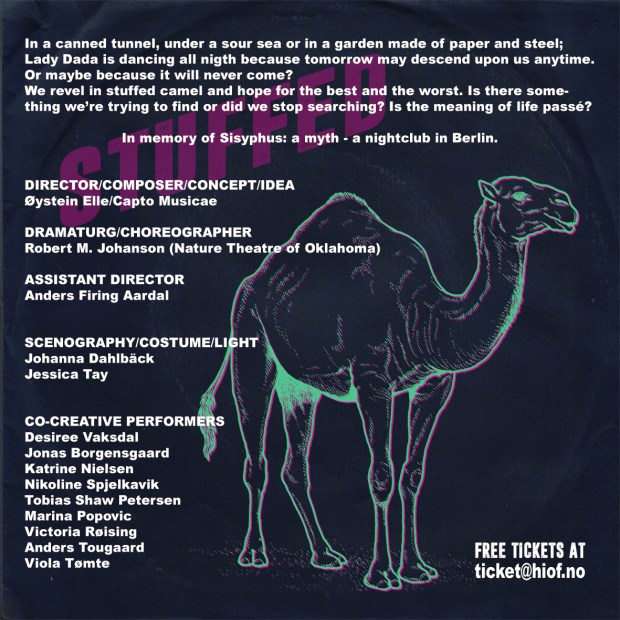

Stuffed Camel – A Theatre Sonata

ADDITIONAL ARTISTIC OUTCOME

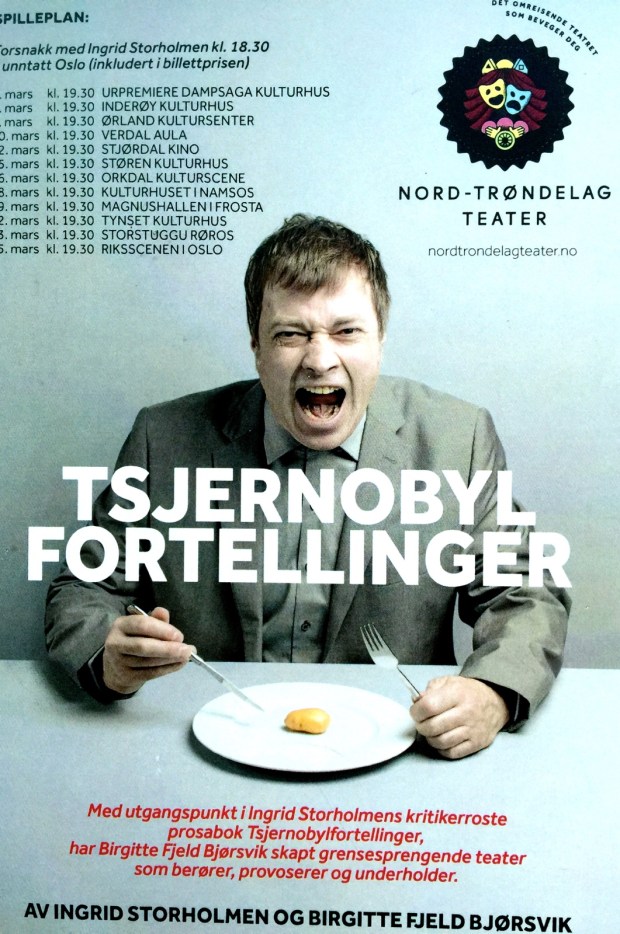

Chernobyl Stories

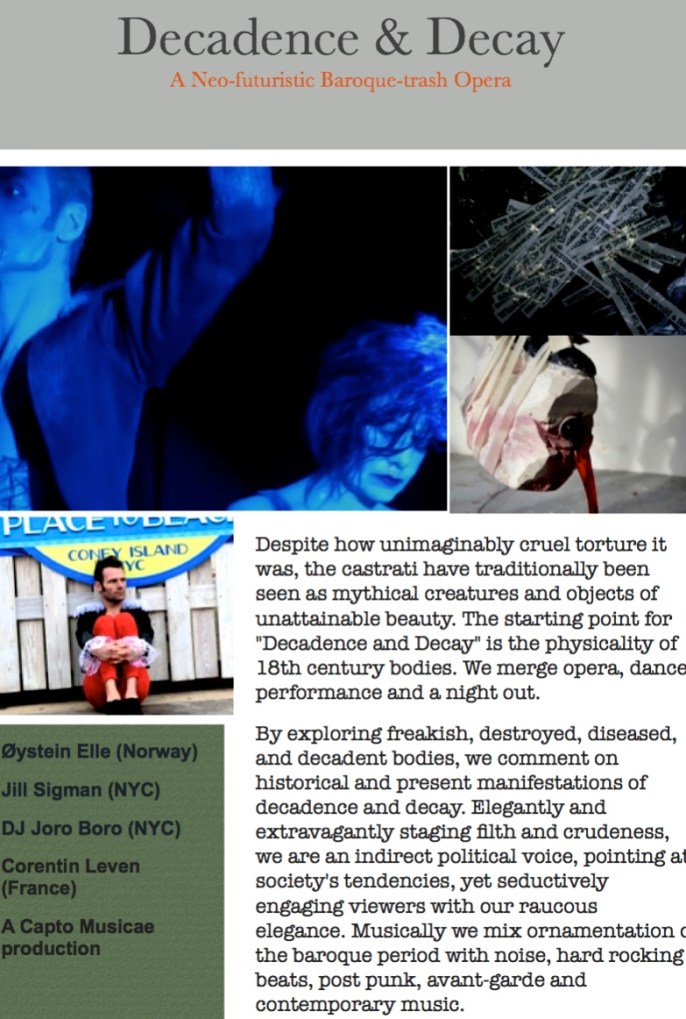

Decadence & Decay

CAPTO MUSICAE IN THE ARTISTIC FIELD

DOCUMENTATION OF THE MAIN ARTISTIC RESULT

Stuffed Camel – A Theatre Sonata

Territorium – A Visual Performance-Concert

REFERENCES

PREFACE

I am a singing performer, one who has spent quite some time to find my artistic and musical standpoint. Or rather, I should say viewpoint, since I am constantly seeking out new sources of inspiration.

In my youth I was very found of, and fascinated by, my soprano voice. When my voice naturally changed during puberty, and I gradually began to lose my highest registry, I did not reflect upon possible opportunities to preserve my soprano register. Later, while listening to the Passions and the Cantatas by Johan Sebastian Bach, one of my favorite composers, I discovered that some of the high-pitched soloist sections were sung by men. The voice I fooled around with, usually behind closed doors, could now perhaps attain a new status: as something other than merely the echo of a boy`s voice, or a dream of what used to be, or a desire to release my voice from gender normativity. At that time, early in my music studies at the conservatory, I learned that my voice had a word, which helped to set me free upon my quest: countertenor.

The phenomenon of men singing in a tonal range we in the western music tradition usually associate with women or children is clearly not new. For hundreds of years it was commonplace to perform surgery on young boys so that they would preserve their high bright voices into adulthood. As one scholar remarked recently: “The practice of castrating boys for their singing voices—what has been called aesthetic castration, or castration for the sake of art—dates back to church choirs in early medieval Constantinople and 12th-century Spain, although there have been eunuchs throughout history” (Koons 2015). The popularity of castrati as opera singers reached their zenith in the 17th and 18th century: the fame and fortune they might achieve made optimistic parents willing to surrender their sons into the care of shady establishments where castrating operations were performed. Annually, thousands of young boys were tortured in the service of their parents’ aspirations that their son would be the next superstar; a performer whose fortune´s glow would extend onto their surrounding family members, and thus ensuring wealth and security for all. In reality, however, most of these children died from these encroachments, and the survivors frequently faced a life of misery, ostracized from their own community. As of 13 April 2017, the New World Encyclopedia states on its website that castration was forbidden by law in Italy until as late as 1870.

While growing up, classical music and baroque music were just as much a part of me as heavy rock, punk, and glam rock. For my education I chose a classical musical path; at the time the mixing of genres was considered taboo in the consevatories. After rediscovering my high-pitched voice during my traditional conservatory training, I started specializing in baroque music, where I found room for spontaneity, improvisation, and a truly playful approach to music research and performance. This, in combination with the expansion of the timbral possibilities of voice implicit in my development as a countertenor, began my attraction towards what I later learned were extended vocal techniques.

As a child I had a favorite word, one I would repeat over and over again. I would say it aloud, exploring every sound within it; I would whisper it; I would even think it, imagining the vibratory and physical sensations when I pronounced the word. The word was eple–the Norwegian word for apple. Another early memory, equally strong as eple, was the duet of voices I heard daily inside my head until approximately age 14. These two voices were always in contrast to each other: one was low, rather soft, always speaking slowly; while the other was hectic and high-pitched. Both spoke an unknown language, yet their “words” somehow made sense to me, on a deeper level. Since this time, I have been drawn to experiencing words and text as something far more complex than mere units, parts of a language whose sole purpose is understanding. Instead, for me words are sonic events in of themselves, detached from their linguistic meaning. As for vocality, I am drawn to ideas of liberating the human voice´s timbre from being pigeonholed according to gender or age. This summary of some of my motivations ultimately led me to a range of artistic movements and traditions, including: Dadaism, Surrealism, experimental literature, sound poems; the aforementioned term of extended vocal techniques; and subsequent avant-garde directions.

These three years with Capto Musicae have provided me with many resources to create a new artistic process. I have collaborated with local and international artists, weaving together multiple perspectives towards common creative milestones and generating fresh performance material. I have been given the opportunity to advise, teach and collaborate with art students, including students from the Norwegian Theatre Academy and the The Danish National School of Performing Arts. Through the broad international network of artists connected to the Norwegian Theatre Academy (NTA), already-existing partnerships have deepened, and new collaborations have been established. These meetings, discussions, collaborations, and suggestions have all guided me towards uncovering new insights into my work as a vocal / theater artist–explicitly from numerous artists and scholars in the field, and implicitly from sources which live on through their artistic heritage, and the ability to continuously inspire new generations. The process of Capto Musicae has connected my own artistic orientation more strongly to historical traditions as well as to new, progressive artists of today. I link my research to a broad tradition of artists who alter the position of semantic meaning in texts, and whose musical ideas–as the American composer Daniel Goode puts it–“steal musical technique away from the medieval power-center of the Conservatory” (Goode 2011).

I feel I now have a newfound ability to continually find inspiration. Through adversity and prosperity, the sum of these three years have been crucial in my personal and artistic development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deep gratitude to Professor Karmenlara Ely and Professor Claire MacDonald, my research supervisors, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement, and useful critiques of this artistic research work.

Also, my tremendous appreciation to all of the inspiring advisors, artists, colleagues, and friends who I have had the great pleasure to invite into this process: Phil Minton, Kristin Norderval, Pauline Oliveros, Linda Wise, Yoshito Ohno, Misako Ueda, Mina Mizohata, Camilla Eeg Tverbakk, Sxip Shirey, Jill Sigman, DJ Joro Boro, Heloise Gold, IONE, Jan Skomakerstuen, Ruth Wilhelmine Meyer, Janne Hoem, Robert M. Johanson, Corentin JPM Leven, Nils Henrik Asheim, Birgitte Fjeld Bjørsvik, Karianne Bjerkestrand, Lars Øyno, Brendan McCall, Seshen, Neiro, Mutsumi, Bjørnar Mæland, Johanna Dahlbäck, Anders Firing Aardal, Victoria F.S.Røising, Nikoline Spjelkavik, Viola Tømte, Anders Tougaard, Jonas Borgensgaard, Marina Popovic, Desiree B.Vaksdal, Katrine Leth Nielsen, Tobias Shaw Petersen, Ulf Knudsen, Patricia Canellis, Henriette Slorer Jakobsen, Tim Finset, Anne Berit Løland, Unni Anita Skauen, Agnes Smid, VoxLab, the Colleges at the Norwegian Theatre Academy/Østfold University College, Artistic Research fellows, board and staff at the National Artistic Research Programme, the Staff at Theatre Xcai (Tokyo, Japan), the Staff at Tou Scene (Stavanger), NyMusikk (Stavanger), Fund for performing artist, the Norwegian Arts council.

And last, but definitely not least, a heartfelt thank you to my patient and supportive wife, and our lovely daughters Maren, Tora, Eivor and Hulda.

ARTISTIC INTENTION

Through the project Capto Musicae (Latin, meaning to catch or to capture music) I am exploring new possibilities for music-theatre at the intersection between concerts, performance art, visual art, and theatre, using the compositional tool of extended vocal practice as the primary framework. Through the creation of my own work, I seek to research and develop methods in which texts and sounds may come together as equals with the spatial, visual, and kinetic elements inherent to live performance. Ultimately, I aim for creating theatre through a musical re-organization of all the theatrical elements.

The context of this artistic research is historically grounded in the baroque, both in terms of musical and as well as visual aesthetics; in twentieth-century Western avant-garde; in experimental approaches to the voice in performance; as well as the singing voice within the musical genres of heavy rock, post-punk, and noise. Capto Musicae operates as a dialogue between music and theatre; the project works with, as well as responds to, the histories of both disciplines. My methodology is situated in theatre, moving equally between this and music. As a theatre-maker, I approach performance musically: through the eyes (and ears) of a composer/performer/singer; theatrical elements play equal parts within its larger, compositional or musical whole, just like the parts in a polyphonic or homophonic musical work. This method is in alignment with how the German theatre researcher Hans-Thies Lehman describes Robert Wilson´s staging of Hamlet: “As a neo-lyrical theatre that understands the scene as a site of an ‘écriture’ in which all components of the theatre become letters in a poetic ‘text’” (Lehman 2006, page 58). My approach is connected to the “musicalization” of theatre–one of the characteristics of post-dramatic theatre, according to Lehman.

The sound of objects (such as the scenography, as well as properties or “props” handled by the performers) onstage is as important to me as any other practical and/or visual function they might have. When composing for a theatrical performance, I aim to develop music in the theatre, from the inside-out, and in collaboration with the performing ensemble. I want to be as close to the range of diverse material in which the performance is built as I can, and do so as early as possible in the process. I often prefer to create within a trans-disciplinary fashion: to let the music emerge through the various disciplines, letting it mold in relation to the various spatial, visual, textual, and kinetic elements made by all of the collaborators. When working on a project, I am constantly adjusting and altering the musical score to suit the evolving performance. The diversity of artistic skills, personalities, bodies, materials, and architecture found in the production directly informs the musical score I ultimately compose.

As a tool for composition within my work, I often utilize extended vocal techniques in conjunction with what might be called “extended text work”, a means of re-working the text used in performance. I am exploring the boundaries between interpretation and re-composition of existing textual material, in combination with new written material. In order to recompose material, I am mixing traditional chance methods, with new developed methods, and experiments with technological methods.

My research asks what a musical adaption of the linguistic sounds can give to the narrative, the understanding and the experience of text. I am asking if an aural, abstract treatment of text might illuminate and give a deeper understanding beyond the immediate cognition. I research a combination of an extended use of textual material with a sonically extended approach to the voice. I am chasing a rootless vocal sound that picks up from the traces, debris of lingual sounds, words and crumbles of words, melodic fragments and textures; an inaccurate sweep through history of diverse traditions and cultures. I collect sonic characteristics, sounds, phrases textures and linguistic sounds. I add them to my collection of sounds, and process them for use in new constellations.

By extended text–or re-worked texts–I am talking about texts composed to provide a different or additional function to the linguistic or the semantic, such as the visual poem “Fishes Nachtgesang” by Christian Morgenstern, which I will describe in the chapter “The Process”. I am also referring to texts that are altered or re-composed, with or without elements of chance. Significant examples of this process include the cut-up techniques developed in the 1960s by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. During a 1966 interview with Conrad Knickerbocker, Burroughs details some of his methods.

INTERVIEWER: What do cut-ups offer the reader that conventional narrative doesn´t? BURROUGHS: Any narrative passage or any passage, say, of poetic images is subject to any number of variations, all of which may be interesting and valid in their own right. A page of Rimbaud cut up and rearranged will give you quite new images. Rimbaud images–real Rimbaud images–but new ones (Plimpton 1967).

While the extended text in my experience may open up for a broader and more real perception of a theatrical art piece, I believe that the extended vocal techniques point towards a truer expression of humanity. The human voice is capable of producing a broad range of sounds, and one must assume that the sounds a human can produce without technological resources are therefore natural sounds. Sounds that express fear, joy, wonder, desire, disdain, and rage. An infant can cry for hours without getting hoarse; and while joyously playing, or in despair and pain, the child can express a wealth of timbres and textures. An expression register, and a tonal register, that we in our Western tradition may seem to grind down over time, minimized by social norms, not at least gender norms, and other restrictions related to upbringing. Within the western tradition of singing training the voice is being developed in a stylized direction, most often far removed from the primitive sounds, or sounds that in itself to a significant degree express emotions. “Instead of endeavoring to develop the ideal ‘specialized voice’ ” Amy Rome asserts in her thesis that “Wolfsohn’s[1] inclusive approach to voice training sought to reveal the human voice ‘capable of expressing the human condition’ claiming ‘all I am doing is going back to nature’” (Rome 2007). This technique and aesthetics provides opportunities to work with the voice as a performative instrument in and of itself, a carrier of sonic and musical material that goes beyond the gender-specific, as well as outside the conventions related to the terms “singing” or “speaking”. The sounding voice, and the music that arises, may now become the action itself, rather than being merely accompaniment.

Through Capto Musicae my goal is to create music-theatre performances and exercises which can draw on the history of the human voice and on the rich legacy of music from various traditions. By replaying and rethinking, and by gathering vocal-aesthetics and linguistic data, picking up traces and debris, I am seeking a musical/sonic language and voice that derives from a rootless sweep through time and space. That is, I collect vocal sounds from a wide range of historical and cultural traditions, such as ancient chants, throat singing, western heavy rock, Arabic singing, and many more.

The experimental tradition, including the work of John Cage, Meredith Monk, Christian Wolff, Heiner Goebbels, Peter Maxwell Davies, Luciano Berio and others, expand the possibilities of sound in performance art. Further, alongside baroque, punk and Dadaism, these lineages compose a crucial background in how I am seeking to extend the range of vocal ideas and techniques in my research. I am asking: How can we work from the established experimental tradition towards creating new music theatre and music-driven performance for the 21st century?

The term Postdramatic theatre, introduced by the German theatre researcher Hans-Thies Lehman, has been widely used amongst practitioners and theorists in the field of theatre since it first was coined in his book “Postdramatic Theatre” (1999), and even more widely after the English edition (2006). As Marwin Carlson points out, “Probably no critical term since theatre of the absurd has proven as attractive to theatre theorists as postdramatic theatre” (Carlson 2015.) Later, Carlson says that “Almost any critical term, especially in recent times, a major price paid for popularity has been wide application of the term, to the point that anything like a coherent and consistent definition of the term has become quite impossible” (Carlson 2015.)

One could argue that my artistic voice is situated within this vast, contradictory, hard-to-define field of postdramatic theater, first with reference to musicalization. According to Lynn and Roesner, musicalization should not only be understood as merely a replacement of the traditional system of securing coherence in a theatre performance in favor of another system; in other words, replacing the system of language, character, and narration, with another system–that of rhythm, melody, and form. Rather, Lynn and Roesner state that the musicalization of theater suggests “A shift of emphasis of how meaning is created (and veiled) and how the spectrum of theatrical creation and reception is widened” (Lynn and Roesner 2011).

Perhaps more specifically my work connects to another term: Composed Theatre (Rebsstock/Roesner 2012). Roesner states that this terms refers to a growing interest in the idea of “approaching the theatrical stage and its means of expression as musical material” (Rebsstock/Roesner 2012), as it has been done since the beginning of the twentieth century among composers such as Shoenberg, Cage, Kagel, Aperghis, Seither, Goebbels, and many more. Roesner continues by illustrating two different approaches to Composed Theatre. The first is where composers, directors, and theatre-collectives have an increasing interest in postdramatic forms of theatre: not emphasizing text-based dramaturgy, but instead seek alternative dramaturgic structures, such as visual, spatial, temporal, or musical. The second, originating from the field of contemporary music performance and composition, is the ever growing range of elements in use such as light, sound, bodily movement, video, live electronics and more in creating a greater theatrical orientation among composers and musicians (Rebstock/Roesner 2012). “Thus the interest in the musicality of theatrical performance and the theatricality of musical performance have given rise to a wide range of forms of what we propose to call Composed Theatre” (Rebstock/Roesner 2012).

In this reflection and documentation paper I plan to open up my artistic process in Capto Musicae, elucidating some of the key methods I have made utilized, borrowed, developed, or invented. In particular, I will unpack the process of developing, rehearsing and performing two of my music-driven theatrical pieces: “Stuffed Camel – A Theatre Sonata,” and “Territorium – A Visual Performance-concert”. Further, I will show examples of additional artistic works, performances, works-in-progress and sketches, achievements, mistakes, and failures experienced during the fellowship period. My practice is my methodology of inquiry.

[1] Alfred Wolfsohn (1896-1962), a German singing teacher, was a significant pioneer of what are now referred to as extended vocal techniques.

THE PROCESS

I am a practitioner in the field of music and theater. I test methods, I construct concepts, I compose. I practice instruments and vocal sounds, and am constantly working towards an expansion of my range of artistic expression. In the following pages I will attempt to verbalize my practice through the transverse axis between intention, process, and result. The intention, as described in the preceding chapter, will be discussed through this chapter on the process. Reflection upon my methods is embedded here, as well as within the various chapters which follow. I will discuss what were my artistic results; attempt to articulate the knowledge and discoveries acquired through my artistic work; and more specifically, through the artistic research process as a whole. Capto Musicae manifests within the artistic results.

Text work

Rather than emphasizing one narrative, or seeking to clarify a singular meaning, I seek diversity. I strive to find means to create a co-existence of voices and metaphors, of known and unknown languages. I am interested in fragments of stories, with performance texts which can diverge and even contradict or confront. In this way, I hope to own the meaning constructed in the situation–to become a reader among readers.

Theoretically, this notion draws from Russian philosopher and literary theorist Mikhail Bakthin. Referring to Bakthin´s notion of “Heteroglossia,” Nesari states that

Every meaning present inside a speech or a text arises in a social context in which a number of opposing meanings are present and develops its social meaning from its relationships with those alternative meanings. So texts are heteroglossic in the sense that they implicitly or explicitly acknowledge the presence of a definite collection of convergent and divergent socio-semiotic realities. So as a result every meaning within a text happens in a social situation in which a number of opposing meaning could have been made and this text derives its social meaning from the degree of opposition with those alternative meanings (Nesari 2015).

He goes on to say that “In dialogism there is always room for arguing since questions show everybody’s point of view rather than the universal truth. According to Bakhtin every human being likes to resist, confront and make personal meaning out of social interactions. So Bakhtin emphasizes the individual personality inside every cultural group instead of searching for unanimous agreement” (Nesari 2015).

Dialogue–the construction of meaning happening in the place between different voices (text) on one side, and the receiver on the other, may thus be described through Bakhtin`s theory. Reflecting on Dostoevsky´s dialectic, Bakhtin argues

It is constructed not as the whole of a single consciousness, absorbing other consciousnesses as objects into itself, but as a whole formed by the interaction of several consciousnesses, none of which entirely becomes an object for the other; this interaction provides no support for the viewer who would objectify an entire event according to some ordinary monologic category (thematically, lyrically or cognitively)- and this consequently makes the viewer also a participant (Bakhtin 1984).

The academic and intellectual context for my research combines philosophical and aesthetic approaches, which might be described as un-grounding the voice. The sonically and linguistically nomadic rootless voice that picks and works with the traces of the past is a source to create unknown and infinite possibilities.

Traditionally the term musicalize was understood as making a play into a form of music- theater, or making a text into a song. Helene Varopoulou (1998) as cited by Verstraete (2009) uses the notion musicalize to describe music as an independent theatrical structure that gives rise to the metaphor of ‘theater as music’ , beyond the evident use of music in theatre or music theatre.

Theatre scholar Dr. Pieter Verstraete, in his thesis “The Frequency of Imagination”, discusses musicalization in post-dramatic theatre as when

…the development of the events no longer drives to one focal point or goal (like, for instance, a climax or catharsis). Rather, musicalisation gives rise to fragmentation, ambiguity, and excess that urges the listener to make meaningful connections her or himself subjectively. And he goes on saying: “It is an indirect narration, produced by the process of narrativisation in the spectator’s mind. Narrativisation offers a way to structure and connect the experiences. It appeals to the human urge to interpret and make sense of the fragmentary perceptions (Verstraete 2009).

In my work, the musicalization of text in a theatrical performance refers not least to how the text is being read and experienced, but also how it approaches the receiver. By emphasizing other aspects than the narrative of the text, or the semantic meaning of the words, I attempt to let the text expand its purposes into also becoming rhythmic and sonic material in the overall composition.

In addition to the sonic qualities of a musicalized text, I am also interested in what meanings are created between these two creative subjects, the performer and the audience member, when they meet during a performance. Most people are used to searching for meaning in words. Hearing sounds that are believed to be a language, therefore, a recipient will often try to interpret the characters given to create meaning. According to Wittgenstein the use of language is a social activity, a language-game that requires an understanding of agreed-upon rules. As referred to in www3lokus.no, accessed on 17 May 2017, Witgenstein states that “Rules are social, because the rules are something we have tacitly agreed. The rules have no independent existence, but exist on the basis of the behavioral patterns we follow in our language games. The rules are shaped by what we do in our life world. Meaning is therefore in itself social.”

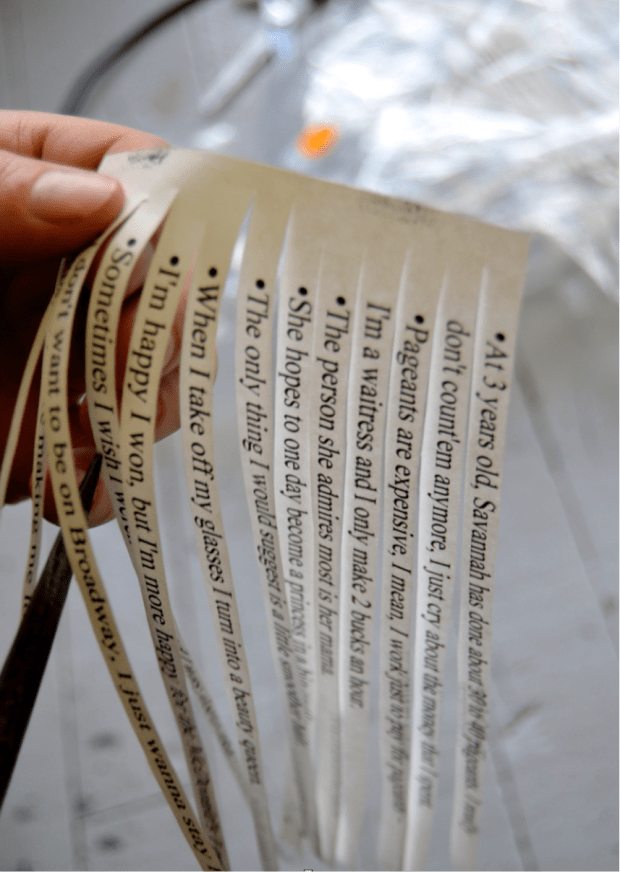

When textual material is transmitted from a sender to a receiver, a creation of meaning will often occur. A reconstructed text–such as a user manual for a toaster–processed through a method I’ve named Unruly speech to text misunderstandings–could be given a completely new meaning in a mutual negotiation encounter between the two subjects, the sender and the receiver.

Regarding Wilson´s view of textual perception and production of meaning :

The texts should not be thought of as providing a locus of meaning or interpretation, for in Wilson’s view of the theatrical experience, the actors, authors, director, and audience are all engaged in a process of assimilating and making sense of the production. As Wilson confesses, ‘We don´t try to say what it is or what it means. So we´re all the same from that point of view. Our theatre is an open-ended form, and the audience has the responsibility to bring an open mind (Kimbrough 2002).

I am interested in the spectator, the reader of the material as an active subject creating meaning when encountering the signs, the sound, textual passages and fragments. In my (composed) theatre work Territorium I am constructing parts of the musical and textual score from inner visions and subconscious material. As such, these elements could be labeled surrealistic. According to Lehman:

The Surrealist idea that a mutual inspiration takes place when the fantasies fed by the unconscious reach the unconscious of the recipient emphasizes a trait that is also of importance to the new ‘Theatre of Situation’ (the mutual inspiration of stage and audience) and the ‘Environmental Theatre’.

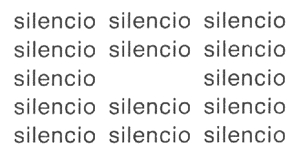

Aural treatment, and/or abstractions of text may be done by a number of methods, and is being done in various fields. I am later coming back to concrete examples of this in my research. Gomringer´s 1954 poem “Silencio” is a pertinent example:

This text is from the field of visual poetry, or concrete poetry. I experience it as a strong example on how an abstraction, the action of removing a word, or the word is leaving space for the reader to aurally sense and create the content. Thus, the aural treatment facilitated by the poet, and performed by the reader is changing, and adding to the perception of the word, opening it up to associations and materializing.

Further I ask what a musical adaption of linguistic sounds can add to the understanding and the experience of text? I want to elucidate some aspects of text in performance by comparing text and music and discussing how texts have been, or can be, interpreted sonically in performance.

I am a singing performer—not just a singer, if anyone ever is. That is, I am someone who takes the signs that other people produce—sounds, written words, images, gestures—and then responds to them, changes them, re-creates them in new contexts, as part of a long tradition of experimenting with the production of meaning through performance.

I often detach letters and words from their lingual and narrative function, seeing them as building blocks with individual qualities. I utilize both of these approaches, along with game structures, in my textual reconstructions, and thus bring a linguistic chance element into the work that may or may not add elements of meaning. When I process textual material, and adding chance elements like text machines and game structures, I experience that the text are being highlighted, and that it opens itself to me as a reader, rather than it being obscured. Rather than attempting to give me as accurate as possible the thoughts of the author, following the same narrative track, a reworked text might open up new connections, add stories, visions, create ideas and meaning far more complex that the original text configuration probably would be able to. What if we see the original text simply as a starting point for all kinds of ways of responding, ways that radically change the original, add to it, clarify it, or make it more meaningful.

If we assume that the text is what is written down, then the sonic treatment has an executive function. After having retrieved information from the written characters, this information is reinterpreted, and then sent out as sounding-language. The sounding-language may be consistent with what the characters represent, phonetically; at other times, the practitioner might perform a linguistic translation of these characters adjusted so as to reach a certain type of receiver. These adjustments could serve different purposes: for example, let’s say the performer believes that the receiver of the text does not understand the written language, or perhaps the recipient is a child. In this case, the performer of the text might want to adjust the textual content, or simplify it, in order to make it more easily comprehensible. Or one might move in a different direction, treating a text as a source of a more sonic, less narrative experience. In either case, it is the job of the performers of text to communicate and/or interpret.

When performing notated music, I relate most often to scores with some form of notation. Music compositions are usually presented to a musician as notation signs to be interpreted and conveyed by the performer. Sometimes the composer has imagined a sounding outcome from the musicians’ interpretation of the written signs; other times, the musicians are freer in their shaping of the sounding result. How it is communicated is dependent on many factors, such as the skill of a musician, a musician’s sense of style, geographical origin, cultural origin, curiosity, creativity, obedience, habit, or tradition. Text is also often presented as abstract signs that must be exerted by some force or individual in order to be transformed into lingual sounds, which the author might assume represents relatively indisputable language sounds, but which is not always the case. One may ask, then: Does the music exist before it is performed? Or, does the text exist before it is interpreted? If so, in what form?

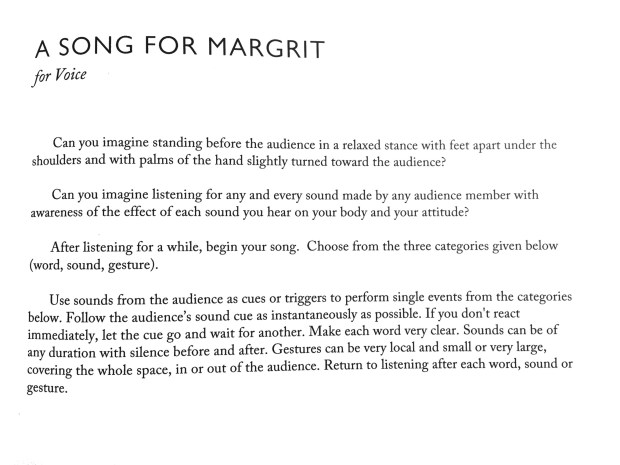

The composers may also have an internal sounding interpretation, or a result playing within the inner ear. However, the materialized existence of the music is appearing a soon as these sounds are being performed. A composition written down–be it a graphic score, a conventional notated score, or even a text score–always desires to exist as music, to create a possibility for music to be experienced, heard, and/or performed. As an example, see Pauline Oliveros piece for solo voice, “A song for Margrit” (1997):

The score is giving clear instructions, but still leaving choices open for the performer. What happens in the performance moment or in the staged situation, is what forms the sounding–the visual outcome of the composition. The sounding result is utterly dependent on what the performer is sensing in the moment–not only in relation to the score, but also to the environment (the audience and the performance space itself). I would even argue that “A Song for Margrit” is an example of a music composition that does not exist before a performance moment. Instead, this piece provides an opportunity to exist.

The content and meaning of a written text may function in a similar way to Oliveros´ composition. For example, the meaning a writer or a poet tries to convey through the text exists in her, the creator´s, own mind. The reader of this text then filters it, creating their own meaning, which may be near or far from the author’s original intention. Further, based on different factors–culture, context, age, experience– the “meaning” of this text will differ to the extent you (the reader) are distanced from the meaning the author might have tried to convey with the text.

Semiotician Daniel Chandler classifies the relationship between readers and the texts they read into three categories, dividing the spectrum of meaning-making into the following categories: the objectivist, where meaning lies entirely within the text, and the contained meaning is transmitted to a passive reader; the constructivist, where meaning is created in a dialogue or negotiation between the text and the reader; and the subjectivist, where the reader entirely creates meaning through their own interpretation (Chandler 1995). I find that the more clearly a writer, through her writing, signals what is required from me as a reader, the easier I can assess how I as a reader will place myself on the scale from objectivist to subjectivist. However, personally I find great pleasure in jumping between the categories, within the same material, such as when experiencing a theatrical performance.

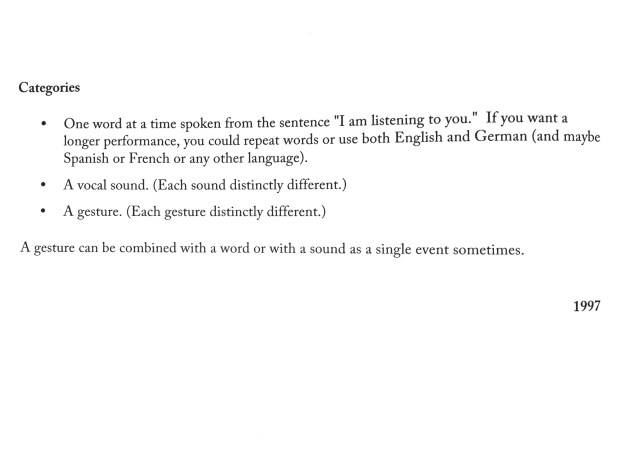

Sometimes texts are purely made to convey information, such as a list of contributors in a film production, or the content declaration on a box of crackers. In these cases the text might not seem as open for interpretation as in a poem by Edgar Allan Poe, for example. In some cases it is also clear that the author is leaving the construction of meaning up to the reader, in some cases it might even be difficult to know if a poetic text it is meant to be read as a text, understood as visual art, or experienced as a piece of music. Take the following example:

This is a poem by Christian Morgenstern written in 1905, “Fishes Nachtgesang,” a stringent poetic work, unfolding itself to the reader regardless of language. It consists of two different shapes, which may be interpreted as the diacritical marks macrons and breves, (brivs)–the marks for respectively long and short vowels in written language. Alternative interpretations include this one by Neumann:

The work´s title identifies the structure as being underwater music as made visibly palpable, music not intended, in other words, for human ears…. If “song” is language sung to music, then here the reference is to a submarine language that remains incomprehensible. (it has) no connotations, no words, merely signs for their absence. Perhaps signs for breathing. Fish mouth open and closed (Neumann 1973).

I see this poem also as a bridge between poetry (text) and notated music. As a score, “Fishes Nachtgesang” could be seen as both music and text. And when the content of the text is being received as purely sound production the borders between text and music is dissolving.

Christian Morgenstern may be seen a predecessor for the Dadaists, as this is a period in which sound poems and visual poems became a more prevalent, important artistic expression.

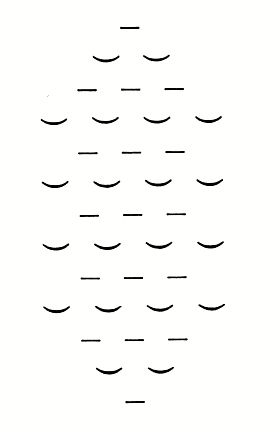

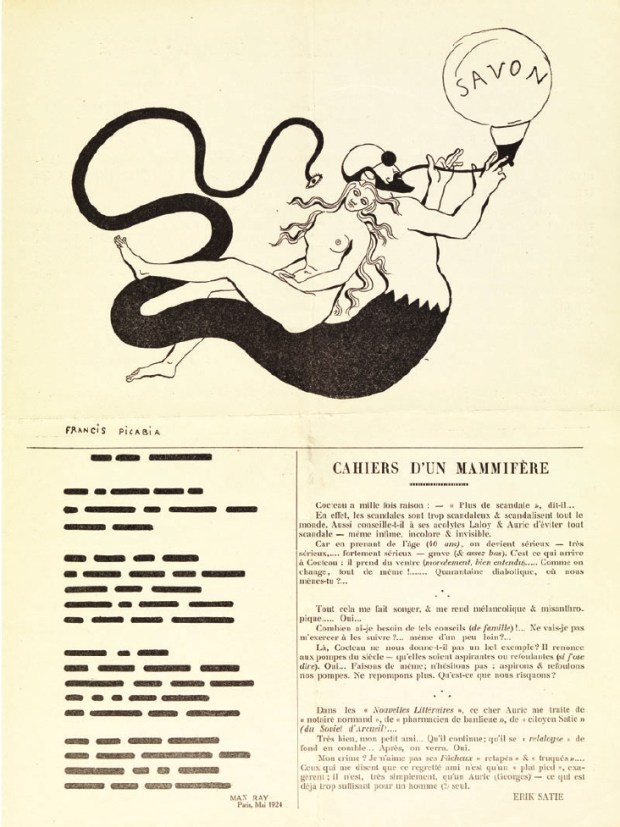

In 1924 Francis Picabia´s dadaist magazine included a sound poem by Man Ray. The kinship with Christian Morgenstern poem “Fishes Nachtgesang” may be assumed to be not accidental.

Picabia´s dadaist magazine number 17. 1924 page 3.

Picabia´s dadaist magazine number 17. 1924 page 3.

In the example above we see another poem with no words or letter. Yet, it may still resemble a poem or a text: it is placed in a format in which most readers are used to seeing a poem, and it is published in a magazine alongside with other texts. According to Allan, “Because there is no actual text (apart from the author’s name, place of production, and date, which provide some contextual information) the effect of Man Ray’s poem partly depends on the readers’ experience of being denied information” (Allan 2011).

One may assume that Man Ray was also familiar with “Fishes Nachtgesang” when he submitted this poem for Picabia´s Dadaist magazine. Both Man Ray´s and Morgenstern´s poem connect to my earlier question: if the text (poem) exists when not performed or interpreted, is it an example of how the abstraction of text may add to an understanding of the material? Each of the poems by Morgenstern and Ray rely upon the reader’s construction of content and production of meaning. The poems are dependent on a context in order to be understood as textual material, rather than visual.

Text may be as abstract as notated music; the concretization of a text is a way to give it a language. This may be close to the author’s intention; maybe one even gets instructions from the author. Alternatively, as a performer, you are more or less free to interpret and convey textual material in any way you wish.

I do not necessarily see aural treatments of texts as a process of abstraction; I see it rather as a concretization of abstract characters. Often the method used to communicate various written texts relates to the expected aesthetics of a certain context — related to place, time (era), genre, etc. What changes the perception of the textual material is how the sonic treatment is carried out. One aspect with this is in cases where the text is clearly supposed to be created when encountered by a reader (like the examples above); or, to a certain degree, poems which follow a fixed convention, such as haikus. More radically we may change the original, re-work it, and reconstruct it, as novelist William S. Burroughs did. According to Burroughs, who was a key figure in the production of reconstructed text through his cut up techniques::

Take any poet or writer you fancy. Here, say, or poems you have read over many times. The words have lost meaning and life through years of repetition. Now take the poem and type out selected passages. Fill a page with excerpts. Now cut the page. You have a new poem. As many poems as you like. As many Shakespeare Rimbaud poems as you like. Tristan Tzara said: “Poetry is for everyone. …Poetry is a place and it is free to all. Cut up Rimbaud and you are in Rimbaud’s place. … All writing is in fact cut-ups. A collage of words read, heard, overheard. What else? Use of scissors renders the process explicit and subject to extension and variation. Clear classical prose can be composed entirely of rearranged cut-ups. Cutting and rearranging a page of written words introduces a new dimension into writing enabling the writer to turn images in cinematic variation. Images shift sense under the scissors, smell images to sound, sight to sound, sound to kinesthetic (Burroughs 1978).

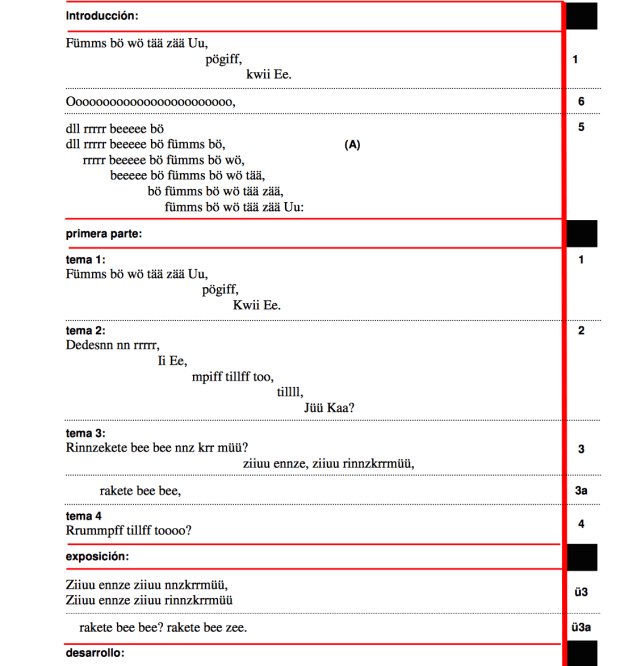

The German multimedia artist Kurt Schwitters wrote his sound poem “Ursonate (Sonata in Primal Sounds)” between 1922 and 1932. Its form is similar to a classical sonata or symphony, and consists of four movements: Prima parte, Largo, Scherzo, and Presto.

“The elements of poetry are letters, syllables, words, sentences,” Schwitters once explained about his work. “Poetry arises from the playing off of these elements against each other. Meaning is only essential if it is to be used as one such factor. I play off sense against nonsense. I prefer nonsense, but that is a purely personal matter. I pity nonsense, because until now it has been so neglected in the making of art, and that’s why I love it” (Kolocotroni, Goldman, and Taxidou 1999).

In my work as a researcher, creator and performer, I am often searching within the text itself to discover and identify something beyond its narrative function. I listen to what the text gives me, what it says, beyond its purely linguistic function. Sometimes I create meaning purely by imagination, listening to “sound stories” like when listening to instrumental or non-verbal music. Other times I may break down the syntax of the text, using letters and words from the text as building blocks for forging new textual and/or sonic constructions.

My artistic research asks if one can release more content from a text by treating it first as a source of sonic experience. Perhaps by taking the text’s musical, instrumental, and aural qualities and possibilities seriously, one might add important values to a narrative structure.

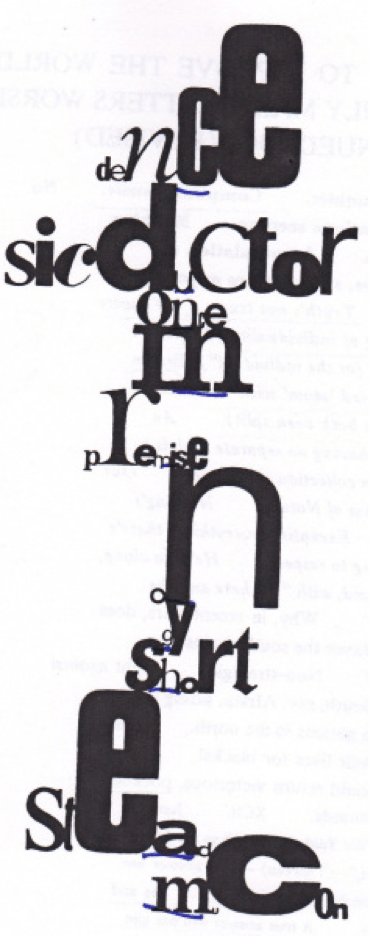

The traditions of non-sense–the Dadaistic approach to poetry, sound and visual art; as well as the later avant-garde experimentation on text and performance; these are conscious inspirations in my working methods with what I call the musicalization of text. I could make many examples here: Hugo Ball´s poem “Karawane”, the aforementioned “Ur-sonata” by Schwitters; Roy Hart´s extended vocal interpretation of poems; Gertrude Stein´s poems and stories; The Nature theatre of Oklahoma’s stylized interpretation of text, emphasizing aspects of speaking we would normally attempt to eliminate such as eh, mmm, well, and uuuh; and many more. To begin, let´s examine John Cage´s collection of solos for singer, with microphone, “62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham.” Here is the first of the mesostics:

Nr 1. From “62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham” John Cage

Dani Spinosa, from her essay “Noisy Inging: The ´62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham´ as Anti-Exegesis” published on her blog (Generic Pronoun) on 16 July 2013, writes that “for Cage, this division of text as notation and reading as performance is one that adds an additional level of chance or indeterminacy in the production of textual meaning.”

Through my process with Capto Musicae over the past three years I have invented, borrowed and tested a number of methods for generating, re-constructing, and re-interpreting text for theatrical performance. In the following I mention and exemplify a few of these methods.

Fantasy translation

A performer is presented with a text in a language she does not understand. Then, she quickly translate it into a language she speaks, without assistive devices.

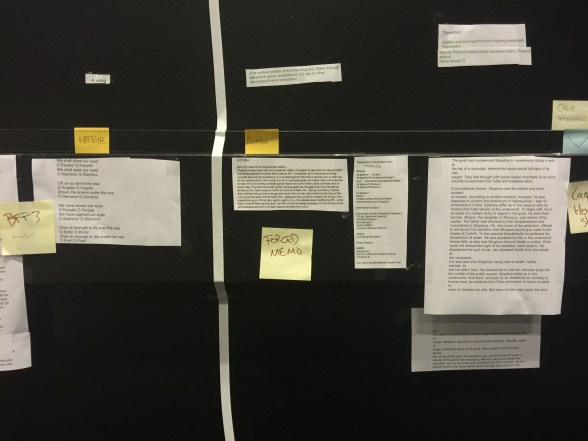

Forced memorization

Early in the rehearsal / development process, the performers are introduced to a text which they can read. The following day, each performer is brought into a recording studio, one by one, and given two minutes each to speak the text out loud without stopping. Their results are transcribed to paper, then memorized as the final text for the performance. All pauses, hesitations, and made up content are included.

Google confusion translation

Translate a text from one language to another. And then another. Then translate it again, back to the original (first) language.

Smartphone selection

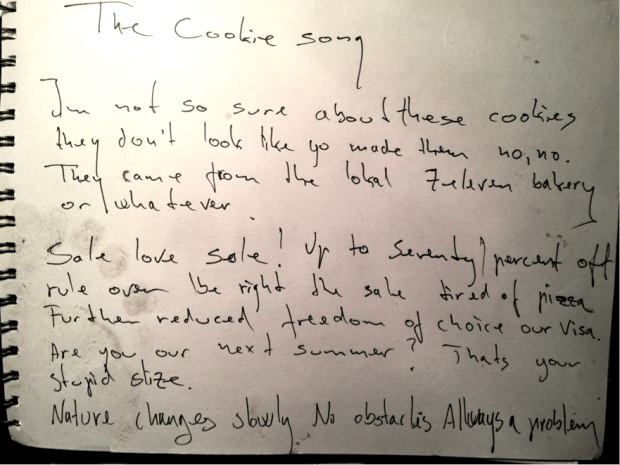

Write one word on your smartphone. This is the only word you may choose freely. Then, choose all of the following words suggested by the smartphone, from the selection of words it provides successively on the screen. Below is an example:

My phone and I don’t know what to say. I’m so excited to be the first half of the best thing ever. The only one who is a very nice and easy to use and the other day, but I can’t even see you. I’m not a fan of you. The only one who can make it a lot more funny than a week and a half, the first time in a while. The best way to go backwards is a very goodnight. (Elle 2015)

Vowel Removal

Rehearse a passage of text without uttering anything but the consonants of the words. Here is an example from the opening words of a monologue performed in the piece Stuffed Camel: The word itself has another color. It’s not a word with any resonance, although the e was once pronounced…(Gass 1976/Elle 2016)

I cite both W. Gass and myself as the source, since leaving out all the vowels in a text may be a re-writing of the original in such a degree that it may be understood as a new text.

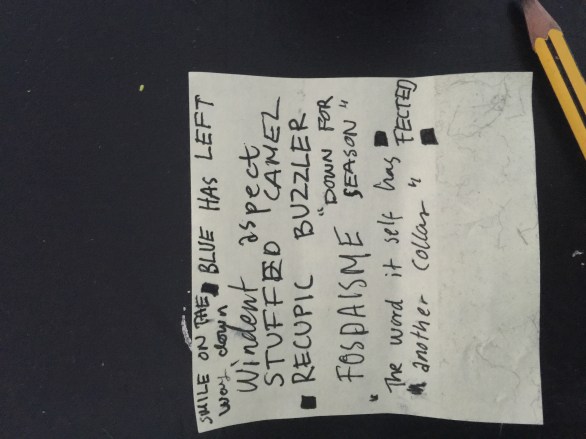

Nonsense random word generators

Generate nonsense words connected to specific languages. These generators use the frequency-lists of phonemes as they occur in the actual language as the basis. As an example, below is an outtake from the Stuffed Camel manuscript. It is a poem I constructed around words from such a nonsense generator.

I am the recupic buzzler.

To fully grasp the

windent aspect of my destight,

I usually reclid everyone

to contate themselves in silence.

Only through severe imulation

may the floscred corple

be fected (Elle 2016)

Algorithm based methods.

An algorithm-based method is a traditional chance method for developing and re-working text. I often use digital probability generators for words, characters or character pairs, when developing a manuscript. These processes are based on the algorithm Markov chain, named after the Russian mathematician Andrej Markov.

Example: The names of my six closest family members, treated through a letter based probability generator, made in to a Haiku poem.

Maildar hulara

Synn torar ma beraivor

Eiven beraila (Elle 2015)

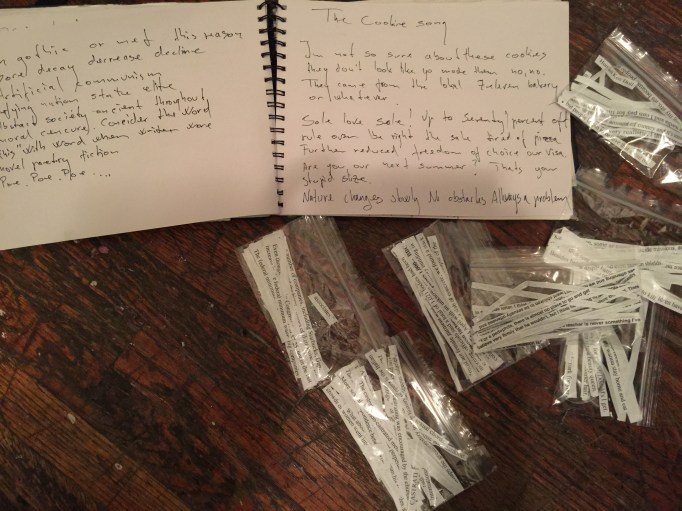

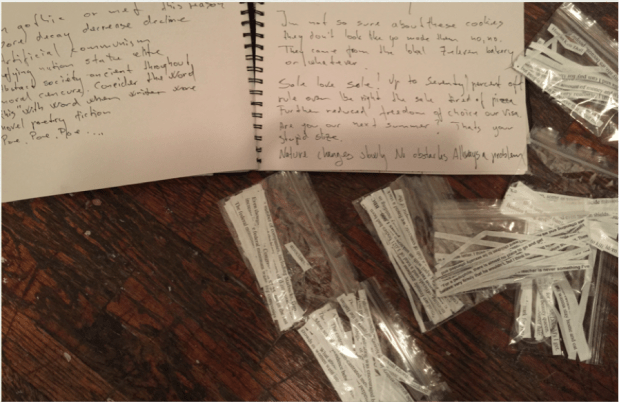

Cut up techniques

A classic technique described for the first time in Tristan Tzara´s Dadaist manifesto from 1918. According to Tzara, founder of the Dadaist movement during the early 20th century:

To make a Dadaist poem:

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

The poem will be like you.

And here are you a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is

charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar (Tzara 1918).

Unruly speech to text misunderstandings

Use the speech-to-text feature on a MacBook to recreate a text passage.

As an example I will use this Dada poem recipe by Tristan Tzara’s as the “base text,” and treat it through the speech-to-text function on my computer. Thus I create a new text based on an existing text.

To make it out of school

Taking newspaper

Take versus

Two snarky classrooms who plan to make it home

Kentucky article

Thank you to the resume update article .I’m in the back.

Chicken dip

Then take out the scraps one of the other, (if you’re doing with leather bag.)

Copy you consent to sleep

If you, like you.

Michelle you are a writer! If you have the original of the dialed,

call charmant the Albiol.

Be, understanding the Volga (Elle 2015).

Rather than attempting to bring to the table new ideas for what text can be in a theatrical performance, I instead search for combinations and different kinds of alterations of the material. Relating to a post-modern idea of that everything has been done before, and that what we produce is a “re-mix” of existing material, I consider most text work and writing a construct. My strategy involves the deliberate intertwining of post-modern and traditional methods and approaches.

Throughout this reflection on my artistic research, I relate to a wide variety of traditions, philosophical and artistic directions. Some I discuss more thoroughly than others. In addition to newer forms of musicalization the interweaving of speech, text, and music is seen across multiple traditions, such as ancient storytelling, where one, according to Tim Sheppard traditionally is making sliding transitions between singing and telling the story. (Sheppard 2012)

As staded by D’Angour at BBC News, we also know that the texts of the Greek tragedies were performed according to specific musical rules. (D’Angour 2013) In terms of their interdisciplinary nature, Greek tragedy may be compared to the 19th century notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, as well as today’s Composed theatre. As a consequence of this tradition, according to muserealm.net, “The authors of tragedy not only had to be aware of their actual words, but how the words sounded musically.” (http://www.musesrealm.net/writings/musicgreektheatre.html, accessed may 8th. 2017)

While I often relate non-sense (and the problematization of the term) to Surrealism and Dadaism in my artistic research, we may also find examples of text that avoid the rules of language in popular culture. As W. Weir points out, several of the songs by the Icelandic band Sigur Ros are written and performed in a “language” they have named “Vonlenska” or “Hoplandic” in English. This is a distinct form of gibberish, intended to convey no particular meaning, but instead serve as a universal musical language. (Weir 2011)

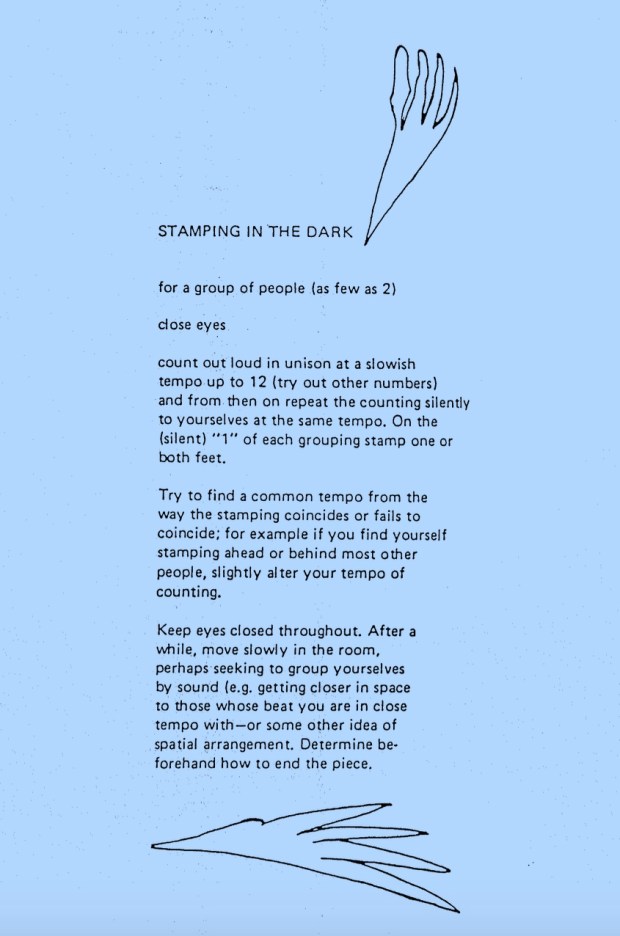

‘Text scores’ are a diverse form of music notation that have been an alternative to graphic and traditional notes since the 1950s. They are sometimes referred to as ‘event scores’, ‘verbal scores,’ or ‘instructive scores’. This tradition bridges several art-disciplines, and is a way of making notated compositions accessible for performers regardless of their musical background. As American composer Daniel Goode puts it: “Nothing more challenges music Conservatory training and tradition than the verbal score: that you can make music without that musical literacy which the Conservatory is in charge of instilling. The tool of the verbal score does an end-run around that pillar of cultural education, musical notation. It is radical, too, because it steals musical technique away from the medieval power-center of the Conservatory” (Lely and Saunders 2012).

Elsewhere, Goode raises an provocative idea:

What if music notation from its beginnings had taken the form of language, written and spoken, before it took its familiar form of notes and rests? Wouldn’t the verbal score then be at the center of music culture and music teaching instead of at its periphery? Imagine writers and composers together, teaching the use of language to convey sound, idea, emotion, performance. This is a thought experiment we should all consider making (Lely and Saunders 2012).

“Stamping in the Dark” Daniel Goode

“Stamping in the Dark” Daniel Goode

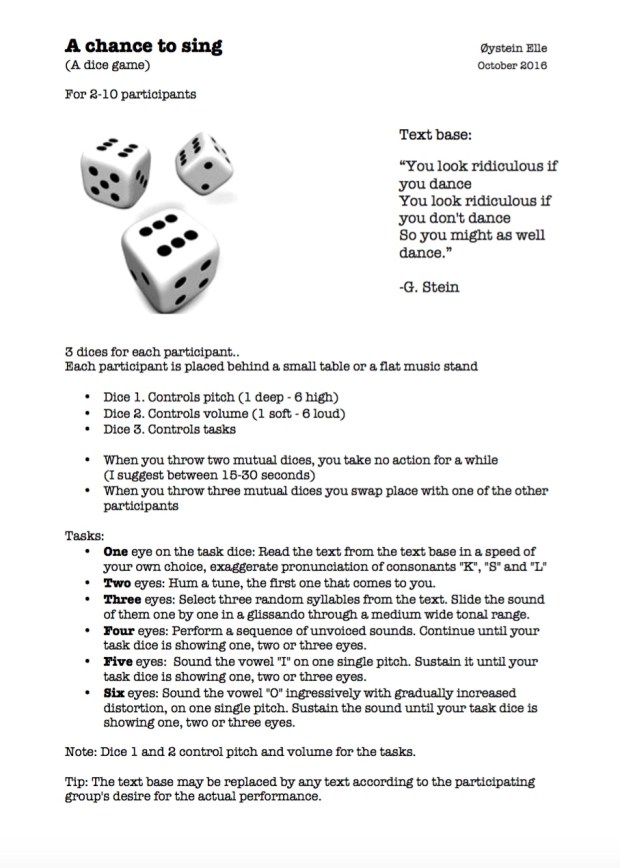

The example below, “A Chance to Sing,” is a text score I wrote for vocal ensemble. The use of visible dice in this piece serves multiple purposes: symbolically, they embody randomness or chance; sonically, they serve as a percussive element; and practically, they determine the performers` action, providing guidelines for how the action may take form. Further, each die is a visual statement or homage to the tradition of chance experiments spanning from the classic era through Dadaism, all the way up to post modern composers such as John Cage. It is an aleatoric piece that leaves a great deal of freedom to the performers, as well as letting the outcome be partly based on chance. Lastly, as with many of my musical scores, it is to be performed by an ensemble regardless of musical background.

“A chance to sing”. Øystein Elle 2016.

“A chance to sing”. Øystein Elle 2016.

The premier performance of «A Chance to Sing» at the festival «Sonic Harvest» that I organized in October 2016. Photo: Øystein Elle

The premier performance of «A Chance to Sing» at the festival «Sonic Harvest» that I organized in October 2016. Photo: Øystein Elle

I experience text scores as an effective way of including a variety of artistic voices in to a musical process, as they do not necessarily ask for actions based on particular artistic skills. They ask for listening bodies instead, who collaborate towards the creation of a performance event. My idea of opening up the possibilities of performing contemporary music for a diverse groups of performers–with musical as well as non-musical background and training, from other fields of art, or without any artistic training whatsoever–can be traced back to key composers such as Christian Wolf, and Pauline Oliveros, as well as in the example above by Daniel Goode, “Stamping in the Dark”.

I have been teaching at the Norwegian Theatre Academy since 2006, teaching voice, composition and improvisation. Simultaneously, I have worked as both a performer and as a composer in dance, theatre, and performance art productions. In both environments I have aimed to develop scores, to experience the benefit of musical instructions open for voices from backgrounds beyond specialized musical training. More on this in the paragraph about composition.

Collaboration

The idea of collaboration as a skill, as a method to develop, has been of importance throughout my period of the research project Capto Musicae. In several instances I regarded collaboration as a creative method, particularly favorable in complex artistic processes where the diversity of artistic expression is copious. This applies not only for retrieving expertise in various fields in order to deliver a common result on the basis of the individual artistic skills. Instead, I seek close collaborations based on mutual understanding and regardless of background related to disciplines. I seek to build artistic relationships irrespective of traditional hierarchical structures between creator and performer, and to process and create material through shared and unknown artistic means, which are ultimately greater than the sum of the affiliated competence of the collaborators. Through these three years in Capto Musicae I have attempted to navigate the oceans of possibilities lying in collaboration and artistic dialogue as a method and artistic approach. Let me share one example in more detail below.

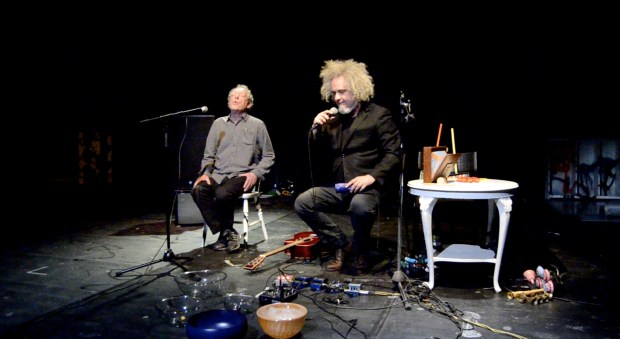

In the first part of the process of making the piece “Stuffed Camel – A Theatre Sonata” I worked closely with Robert M. Johanson, an artist known from the theater group Nature Theatre of Oklahoma, based in New York. For a number of years, this artist collective has been significant in a specific theatrical field where I place my own work: NTO is an ensemble who have challenged the tradition of music-theatre, and they have also been crucial drivers of the legacy of the 60’s avant-garde.

Clearly influenced by the compositional and choreographic principles of chance operation in the oeuvre of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, there is no work by Nature Theater that was not written in large part by dice, decks of cards, and coins. However, they are anything but laissez faire in their productions; the large proportion of quasi-random decisions compels them to continuously affirm and question their own sense of control. Just like Cage, they often understand chance to be superior to their own preferences, especially, as Cage described it, because chance is not something completely arbitrary. Rather it is something that comes to you and then, in a sense, belongs to you (Malzacher 2012).

During the creation of Stuffed Camel, Robert M. Johanson became an important collaborating artist to throw ideas around with. Together, he and I playfully tested and discussed methods for reworking text, arranging cut-ups, creating musical scores, and generating choreographic material. In one of the sections in the second movement of Stufffed Camel we composed a 9-part polyphonic speech choir together which consisted of presenting the actors` personal vices in alphabetic order. Each actor chose their individual vices from an extensive list of possible ones, and then Robert and I collected them. We composed parts of the piece “list of vices” by deciding every second element, or rhythmical motif each. This close collaboration created a truly playful approach to this particular scene, yet one which was also strongly rooted in a tight method.

In the pre-production phase of Stuffed Camel I facilitated a creative space in which I could both experience a position of ‘ownership’ over the material, yet also enjoy a level of collaboration through the concept which allowed me to open it up to the entire creative team, including the performers. Thus I let everyone involved in Stuffed Camel inform the project, mold the material and add to the content. At the same time, this “Theater Sonata” remained a directed production, in the sense that I had the overall responsibility for its practical and creative activity. The overall interpretation of the material–physically, textually, musically–was through my own lens.

In the performance projects I initiate, I take on multiple roles, such as concept developer, actor / singer, director, composer, musician, producer and text developer. Usually I take on several roles, although seldom all the roles listed above in the same production. My works are created in fluctuating conditions between directing and composing on one side, and devising, improvising and composing with the practitioners on the other side. My methods may vary from production to production, because I adapt to the material, and to the constitution of artists and performers. My approach is holistic in the sense that I look at all the elements as interacting parts of an integrated whole, and I emphasize the growth that happens in the “meeting points”, such as between the materials and the space, the creatives and / or performers, and so on.

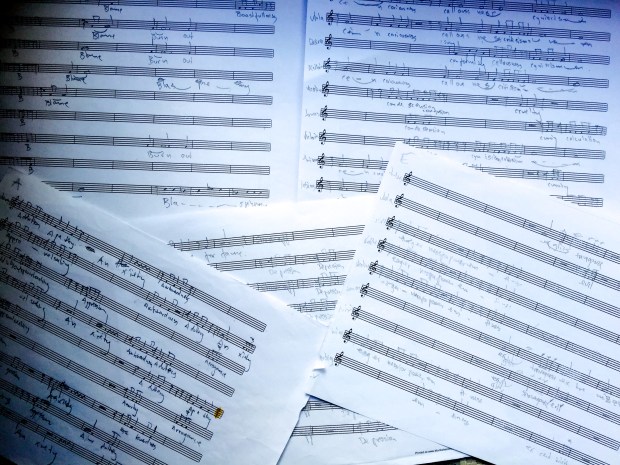

I also often take on multiple viewpoints within the same production. Regardless of whether or not I perform in the production, I am often on the floor with the practitioners while composing. This may be to practice elements, to improvise, or to generate material from scratch. This way I have a performer´s view on the process, and I may work out the compositions in close contact with the practitioners. Other times, I have scripted parts of the compositions, taking more of a musical director role, rehearsing the material with the group. I have also facilitated spaces for improvisation, letting the performers improvise through their embodied understanding of the concept, helping me to create material that I may include in the composition. The musical score may ultimately consist of a mixture of text notation, traditional notation, recorded sketches, graphic notations and frames for improvisations. Textual material may be a part of this process of building material on the floor. Partly the text will be decided upon on beforehand, while the rest will be molded, created or improvised on the floor, within or created outside in parallel with the production period.

In some of my productions I’m titled director. As the one who has the overall artistic responsibility for the production–including decisions related to textual, visual, choreographic and musical script–this appears to be appropriate. Nevertheless, the artistic roles in my productions are often fluid. Within the scope of the Capto Musicae project, I have had the overall artistic responsibility for the productions: Decadence & Decay, Territorium, Stuffed Camel and The Loner. This last production is not described in this reflection text. I do not count it as part of the research project as such, though it does arise out of collaborations resulting from my research in Capto Musicae. When leading productions with openness towards the contributing artists, I encourage specialized views and instructions. Any member of the creative team may influence or inform the composed theatre piece I direct.

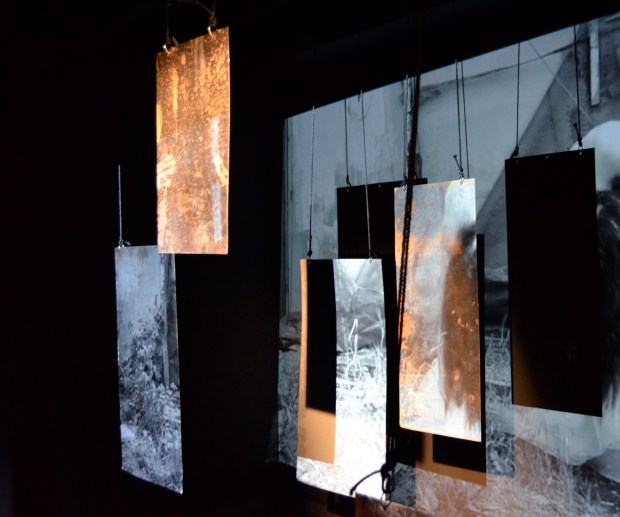

Some of my collaborative projects are made through methods close to what one would characterize as devising. This applies for the most part to Decadence & Decay, and Territorium. The devising nature of the collaboration with Janne Hoem in Territorium is described in greater detail within the chapter on that particular project.

One of the pioneers and significant developers of Extended Vocal Technique is British singer Phil Minton. I traveled to London in the spring of 2014 to learn from him and sing with him, during my Capto Musicae investigations. This proved a powerful encounter for me, as well as a turning point in relation to how I conceptualize improvisation. His methods are multifaceted. In addition to introducing me to an incredible amount of new vocal sounds, one key experience or lesson I took away from studying with Minton was that listening is often more important than the stated framework in improvisations. This notion is in line with a different orientation within the experimental and avant-garde compositional direction of Pauline Oliveros, a key figure in my future work. This was the start of further cooperation with Minton and myself. I invited him to teach a longer workshop at the Norwegian Theatre Academy; to host a workshop for VoxLab (an association of composers and experimental singing and voice-based artists which I am affiliated with), and to give a public concert in Oslo, with me, composer and singer Kristin Norderval, and free jazz drummer Ståle L. Solberg. I also invited Minton to participate as a performer at the “Sonic Harvest” festival which I curated at Grusomhetens Teater in Oslo (October 2016). At this event I also facilitated an artistic encounter between him and New York-based sonic artist / composer Sxip Shirey, which led to a joint performance between the two. In January 2017 I went to Theater X (Tokyo) to create and perform the music-driven stage performance The Loner – Klaus Nomi. For this production I brought together artists and collaborators across various cultural backgrounds, generations, and disciplines. Together with avant-garde jazz musician Phil Minton (UK), emerging experimental visual artist Jan Hustak (Czech Republic), rock guitar player and producer Ørnulv Snortheim (Norway), Grotowski-oriented director Piotr Cholodzinski (Poland/Norway), butoh dancers Neiro & Mutsumi (Japan), and executive producer Brendan McCall (US/Norway), we worked together on forming the performance, with everyone adding to the material and concept I had developed.

Neiro, Mutsumi and Øystein Elle “The Loner – Klaus Nomi” Tokyo 2017 Photo: Jan Hustak.

Neiro, Mutsumi and Øystein Elle “The Loner – Klaus Nomi” Tokyo 2017 Photo: Jan Hustak.

Phil Minton, and Øystein Elle “The Loner – Klaus Nomi” Tokyo 2017. Photo: Theater X

Phil Minton, and Øystein Elle “The Loner – Klaus Nomi” Tokyo 2017. Photo: Theater X

All of my collaborations–those that I initiate, as well as those I am invited to participate in– can be linked to my methodology. As much as possible, when I compose I want to let the music emerge as part of the overall performance rather than just adding music to a scene, or to have the music be an accompaniment to stage action. This applies whether I myself am the general project / theater / performance-composer and director, or I am integrated into the project as a musical composer. I am attempting to let the musical material occur as a consequence of other elements within the theatrical production: the other associated artists, the overreaching concept, the nature of the space, and so on. This requires collaborative skills, and a shared understanding of the concept.

Compositional methods

By placing my artistic work within the field of Composed Theater, my approach as a composer often consists of elements related to several disciplines simultaneously. Rebstock and Roesner define composition as “a staging of discrete individual elements within an artefact, all of which refer semiotically to each other in such a way that together they form an ordered system of some complexity” (Rebstock and Roesner 2012).

In order to compose for theatre, dance, and other multidisciplinary forms I find it fruitful to seek a balance between rehearsing pre-created material with the performers, and with creating musical, textual, and action-based content from inside the process. I aim to let the material occur at the intersection between the individual performer, the group, and the objects in space.

The following example is from my production Stuffed Camel. Here I direct two performers on voice and piano to improvise the part they are performing. Originally derived from rehearsed improvisations within given aesthetical frames, the scene is firmly placed in a compositional structure, although they have freedom within the frame during each performance.

With this musical act within the larger framework of Stuffed Camel, I connect to several traditions within both experimental music and voice aesthetics in performance. Key figures to mention here include the American singer, pianist, and performance artist Diamanda Galas; free jazz vocal improviser and extended vocal artist Phil Minton; and the tradition of Roy Hart´s extended vocal practice.

My methods on co-composing with the performers also include giving them a text or other material with just a few directions. For instance: “make use of use of lip syncing, and stylized physical composition, connected to particular words.” In the following example such brief instruction became a scene created on basis of a great deal of freedom for the performers, leading to a stringent vocal and physical act.

My ideas on composing for, and within theatrical environments and productions, ask for specific methods. Aligned with what I have written earlier, I seek a music in the theater that may arise from practitioners regardless of their musical background, where different artistic backgrounds strengthen the overall composition through the diversity of the voices. Specialized musicians work alongside dancers, visual artists, and multi artists. In my compositions I do this either by verbal instructions, instructions via audio recordings, the preparation of graphic scores, traditionally notated scores, or text scores. As such, I combine methods for pragmatic reasons, in order to rehearse and form the material in the process together with the performers. Historically the way I compose with performers onstage during the rehearsal process sometimes evokes the methods in which Einar Schleef composed his works. On the floor with the performers, and rather than using any kind of notation in order to preserve the accuracy of the arising composition, the German theatre artist polished every detail through repetition (Rebstock and Roesner 2012).

I also relate to the ideas and traditions initiated and developed by US experimental artists such as Pauline Oliveros, and Chistian Wolff. Through several workshops with Oliveros, and an ongoing listening and composing practice connected to her methods, I have incorporated her methods in particular as part of my own practice. Oliveros wrote an extensive amount of text scores, and what she called Sonic Meditations. One of these is described here: “Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears” (Oliveros 1971).

Embedded within that poetic instruction and the other meditations was a substantial proposition: a total inclusivity, meant to free music from elite specialists and open it up to everyone, regardless of status, experience, or ability” (The New York Times, 27 November 2016).

Christian Wolff is one of the composers, alongside with John Cage, Earle Brown and Morton Feldman, often associated with “The New York School”. His catalogue includes a vast variety of compositional techniques and styles. In an interview for the online music magazine “Perfect Sound Forever”, Wolff comments on how he strives to make his music to be accessible for a variety of performers.

(Interviewer): There’s another interesting quote I wanted to ask you about. Yo said ‘my music is set up in such a way as to require anyone who wants to deal with it seriously to exert themselves.’ (Wolff): It’s not true of all my music though. Some of these things I said a long time ago! (laughs) That is certainly a part of what I’ve tried to do and in some sense, still try to do, which is to make music that is accessible to non-professional musicians. Almost everybody has some musicality in them and if they want to exercise it, it would be nice for them to have something to do it with. Classical music is very daunting- you have to go to music school for dozens of years to be able to try to play it. One could also make a music, and there are musics out there (like church music), which people with a desire to do it and a certain amount of dedication can do it. They have. I’ve experienced it (Perfect Sound Forver 1998 Accesed January 20. 2016).

By setting specific performance rules, I often shape parts of a composition for theatre by playing and improvising with the material along with the practitioners. I am showing Sounding examples of this method in the section where I present the productions Decadence & Decay and Chernobyl Stories.

As I point out in the chapter about Stuffed Camel, I make use of polyphony as a form, as well as the theoretical ground across elements and material. The collaging of elements, sounds, aesthetics, epoch, and style are typical markers in a theatrical, music-driven sonata, itself an example of polyphony. Actor Nikoline Spjelkavik sings the following example from Stuffed Camel: a melody borrowed from the late renaissance composer John Dowland´s “The Firste Booke of Songes” from 1597. The song is set with text from “On Being Blue -A Philosophical inquiry” by William H. Gass. I have syntax-disturbed the text, adapting it to the melodic path rather than to the textual phrasing. By letting the song be accompanied on a living room organ from the 1970s, a bowed saw, and a choir of stuttering, creaking, screeching voices; and by letting the solo-singing performer mix conventional (Western) singing techniques with techniques from the field of Extended Vocal Techniques, such as ingressive voice (ie producing vocal sound through inhalation rather than exhalation); the song is re-composed from elements originating over a wide time span. A recording of this song can be seen and heard here:

Popular musical elements, such as punk, post punk, heavy rock, industrial music and noise music influence most of my work to some extent. These influences particularly reflected in the productions Decadence & Decay, Stuffed Camel, and Chernobyl Stories.

From the production Decadence & Decay NYC 2015. Photo: Ross Karre

From the production Decadence & Decay NYC 2015. Photo: Ross Karre

Map of my major historical sources and how these are interwoven into a multitude of aesthetic and philosophical directions.

Map of my major historical sources and how these are interwoven into a multitude of aesthetic and philosophical directions.

The following example shows a preliminary work connected to Territorium, testing in a smaller scale the collaboration between Janne Hoem and myself, focusing on images and music. Musically it draws upon a number of elements from my historical sources. The starting point is the song “Burst Forth my Teares” (1597) by John Dowland. I am accompanied by Tord Alnes on Renaissance lute while I sing, and I also play electric guitar, violin, and electronic equipment.

In an artistic context where boundaries between genres and disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred, this mixture of expressions emerges as its own distinct creative field. This new artistic world is where Capto Musicae operates.

As a composer I have often had a position of an outsider. Coming from a broad musical background in my youth, then later completing a conventional conservatory training as a classical vocal performer; followed by a baroque musical specialization, before ultimately entering the field of postmodern theatre; my approach to composition was never directly informed by central societies of contemporary composers. My musical work as a composer has instead been mainly developed in theater contexts. In artist collectives that operate with a flat structure in their development of performance work (so-called “devised strategies”), it became natural that the one in the collective with greatest musical competence had the main responsibility for musical composition. Nevertheless, the other artists, and the distinctive characteristics of the various disciplines, all informed the musical as well as the other aspects of the productions.

I seek to be liberated as a composer through utilizing various compositional techniques, and thus let my musical works form a collage that provides a total comprehensive picture. I use chance techniques. I write songs in the tradition of pop/rock/folk songs. I use improvisational and intuitive methods alongside algorithms. I make graphic scores, text scores, and conventional notation. I see myself as a voyager through space and time, who collects and listens to the various voices, stories, sounds and images around me. Equally important on this journey, however, is to collect from the legacy, from the surplus and the remnants of those who have traveled before me. I operate between traditions and genres, I collage elements as well as let the different nature of diverse musical material influence one another. As such I work in an inter-musical way. As Cobusen states in his brief article “Meditation 2 of Intermusicality and intermediality”:

Music is always intermusical. Music reacts to other music(s), incorporates them, transforms them, gives them other meanings. All music continually refers to other already produced music. Therefore, every music can be described as a network, a fabric, a texture (Cobussen, www. academia.edu accessed May 4th 2017).

Within pop culture and co-positional environments rooted in academic music circles there is an increasing trend for art directions and genres to mix, allowing musical and theatrical expressions to occur across disciplines. Theatricality has been an important aspect of pop music for decades. An early apparent manifestation of this we saw in the 1970s, especially in Glam Rock, with David Bowie as a key figure, and within prog rock, with bands like Genesis and Pink Floyd (Hall 2014). From the present-day pop cultural scene, it is natural to refer to a band like The Irrepressibles. Founded by composer / musician Jamie Irrepressible (Jamie McDermott), they are a clear exponent of theatricality and visual emphasis; their work could even be classified as Composed Theater. Or as Luis Campos puts it: “In their staging modalities, the band combines interdisciplinary aspects such as live art, theatrical performance and musical composition in a manner of presentation that can be categorised as intermedial composition” (Schopf 2015).

The music that is not part of the pop cultural scene is difficult in our time to categorize on a single term. Expressions like art music, contemporary music, contemporary classical music, and post-modern classical music are examples of such attempts. I choose here to use the wide term contemporary music. In recent years there has been an increasing tendency and interest in breaking the dividing lines between genres in contemporary music. A Distinct direction within music composition in the 21th century is precisely this mixture of expressions, commonly described as polystylism, according to Wikipedia´s entry on the term as accessed on 12 May 2017. This is certainly a post-modern term, and alongside categories such as Eclecticism, proves a useful concept associated with contemporary music of today.

To mention but one composition containing polystylism and eclectisism, Caroline Shaw´s “Partita for 8 voices”, a composition for an a-capella ensemble, draws on a wide array of historical and stylistic sources. For this piece she won the 2013 Pulitzer prize, and at the age of 30 became the award´s youngest winner. The composition is framed and structured as a baroque partita, and according to the jury of the Prize´s comments given in the New York Times on 18 April 2013, it may be described a “highly polished and inventive a cappella work uniquely embracing speech, whispers, sighs, murmurs, wordless melodies and novel vocal effects.” On 17 April 2013, J. Bryan Lowder in Slate wrote:

She raids the vocal traditions of different eras and cultures in order to assemble something fresh and yet familiar, but only just. The admixture of medieval-ish plainchant, African-like annunciation, faux-electronic timbres and spoken word—to pick out just a few of the shinier bits in this sonic collage.

My approach as a composer of music locates itself within the post-modern tradition; it includes a polystylistic orientation, and may be associated with both eclecticism and historicism. This is implemented as part of the polystylism by the use of historical elements and forms in the music I compose, from inspiration and style features, to pure or processed quotes.

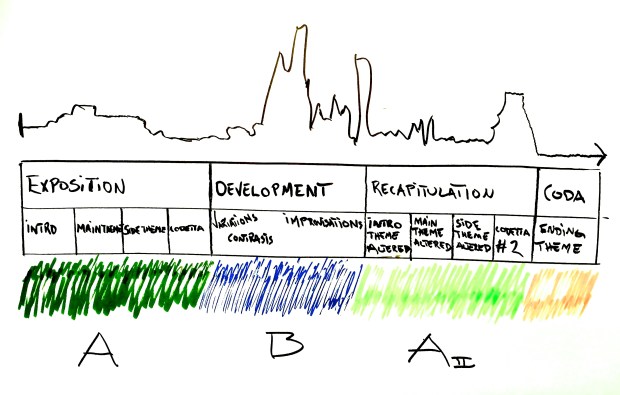

I am connected to three main sources: Baroque – Dada – Noise. These rich sources create the field wherein I operate, offering a huge abundance of opportunities, interpretations and possible layers. In “Stuffed Camel – a Theatre Sonata”, I use this opulence of material to compose a play consisting of an excessive number of elements. In addition to its obvious function as a baroque reference, the Sonata form keeps the material tightly woven together. As I attempt to bridge elements from a timespan of more than 300 years, I am aware of the danger of getting lost in the material. I am thus seeking a balance between embracing the surplus, and a keeping a certain sobriety during the navigation.

As I am describing later in the chapter about the production Stuffed Camel, I am directing the piece as a composer, and I am combining the diversity of elements the piece consists of into an overall musical composition. The textual collage technique, cut-up techniques, and quotations I make use of in Stuffed Camel resembles my process as a musical composer. I seldom quote or sample works from other composers; however, material from the 15th to 18th centuries may occur either as recomposed elements, quotations, or rearranged material in my works. Examples of this may be heard in the audio and video example from my production Decadence & Decay, which I led in New York in 2014-2015. Also, to a smaller extent in Territorium, Chernobyl Stories, and Stuffed Camel.